Making Choices

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can my programs do different things based on data values?

Objectives

Write conditional statements including

if,elif, andelsebranches.Correctly evaluate expressions containing

andandor.Trace the execution of unnested conditionals and conditionals inside loops.

Earlier in our lesson, we discovered something suspicious was going on in our inflammation data by drawing some plots. How can we use Python to automatically recognize the different features we saw, and take a different action for each? In this lesson, we’ll learn how to write code that runs only when certain conditions are true.

Conditionals

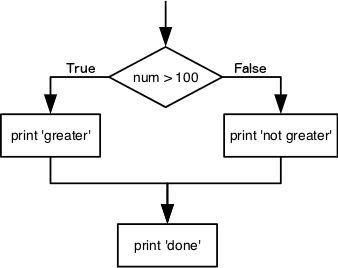

We can ask Python to take different actions, depending on a condition, with an if statement:

num = 37

if num > 100:

print('greater')

else:

print('not greater')

print('done')

not greater

done

The second line of this code uses the keyword if to tell Python that we want to make a choice.

If the test that follows the if statement is true,

the body of the if

(i.e., the set of lines indented underneath it) is executed, and “greater” is printed.

If the test is false,

the body of the else is executed instead, and “not greater” is printed.

Only one or the other is ever executed before continuing on with program execution to print “done”:

Conditional statements don’t have to include an else.

If there isn’t one,

Python simply does nothing if the test is false:

num = 53

print('before conditional...')

if num > 100:

print(num,' is greater than 100')

print('...after conditional')

before conditional...

...after conditional

We can also chain several tests together using elif,

which is short for “else if”.

The following Python code uses elif to print the sign of a number.

num = -3

if num > 0:

print(num, 'is positive')

elif num == 0:

print(num, 'is zero')

else:

print(num, 'is negative')

-3 is negative

Note that to test for equality we use a double equals sign ==

rather than a single equals sign = which is used to assign values.

We can also combine tests using and and or.

and is only true if both parts are true:

if (1 > 0) and (-1 > 0):

print('both parts are true')

else:

print('at least one part is false')

at least one part is false

while or is true if at least one part is true:

if (1 < 0) or (-1 < 0):

print('at least one test is true')

at least one test is true

TrueandFalse

TrueandFalseare special words in Python calledbooleans, which represent truth values. A statement such as1 < 0returns the valueFalse, while-1 < 0returns the valueTrue.

Conditions are tested once, in order.

Python steps through the branches of the conditional in order, testing each in turn, so ordering matters.

grade = 85

if grade >= 70:

print('grade is C')

elif grade >= 80:

print('grade is B')

elif grade >= 90:

print('grade is A')

grade is C

The Python interpreter does not automatically go back and re-evaluate if values used for a condition change within the conditional statement.

velocity = 10.0

if velocity > 20.0:

print('moving too fast')

else:

print('adjusting velocity')

velocity = 50.0

adjusting velocity

We often use conditionals in a loop to “evolve” the values of variables.

velocity = 10.0

for i in range(5): # execute the loop 5 times

print(i, ':', velocity)

if velocity > 20.0:

print('moving too fast')

velocity = velocity - 5.0

else:

print('moving too slow')

velocity = velocity + 10.0

print('final velocity:', velocity)

0 : 10.0

moving too slow

1 : 20.0

moving too slow

2 : 30.0

moving too fast

3 : 25.0

moving too fast

4 : 20.0

moving too slow

final velocity: 30.0

Compound Relations Using

and,or, and ParenthesesJust like with arithmetic, you can and should use parentheses whenever there is possible ambiguity. A good general rule is to always use parentheses when mixing

andandorin the same condition. That is, instead of:if mass[i] <= 2 or mass[i] >= 5 and velocity[i] > 20:write one of these:

if (mass[i] <= 2 or mass[i] >= 5) and velocity[i] > 20: if mass[i] <= 2 or (mass[i] >= 5 and velocity[i] > 20):so it is perfectly clear to a reader (and to Python) what you really mean.

Tracing Execution

What does this program print?

pressure = 71.9 if pressure > 50.0: pressure = 25.0 elif pressure <= 50.0: pressure = 0.0 print(pressure)Solution

25.0

Trimming Values

Fill in the blanks so that this program creates a new list containing zeroes where the original list’s values were negative and ones where the original list’s values were positive.

original = [-1.5, 0.2, 0.4, 0.0, -1.3, 0.4] result = ____ for value in original: if ____: result.append(0) else: ____ print(result)[0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1]Solution

original = [-1.5, 0.2, 0.4, 0.0, -1.3, 0.4] result = [] for value in original: if value<0.0: result.append(0) else: result.append(1) print(result)

Initializing

Modify this program so that it finds the largest and smallest values in the list no matter what the range of values originally is.

values = [...some test data...] smallest, largest = None, None for v in values: if ____: smallest, largest = v, v ____: smallest = min(____, v) largest = max(____, v) print(smallest, largest)What are the advantages and disadvantages of using this method to find the range of the data?

Solution

values = [-2,1,65,78,-54,-24,100] smallest, largest = None, None for v in values: if smallest==None and largest==None: smallest, largest = v, v else: smallest = min(smallest, v) largest = max(largest, v) print(smallest, largest)

Checking our Data

Now that we’ve seen how conditionals work,

we can use them to check for the suspicious features we saw in our inflammation data.

We are about to use functions provided by the numpy module again.

Therefore, if you’re working in a new Python session, make sure to load the

module with:

import numpy

From the first couple of plots, we saw that maximum daily inflammation exhibits a strange behavior and raises one unit a day. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to detect such behavior and report it as suspicious? Let’s do that! However, instead of checking every single day of the study, let’s merely check if maximum inflammation in the beginning (day 0) and in the middle (day 20) of the study are equal to the corresponding day numbers.

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')

We also saw a different problem in the third dataset;

the minima per day were all zero (looks like a healthy person snuck into our study).

We can also check for this with an elif condition:

elif numpy.sum(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) == 0:

print('Minima add up to zero!')

And if neither of these conditions are true, we can use else to give the all-clear:

else:

print('Seems OK!')

Let’s test that out:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')

elif numpy.sum(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) == 0:

print('Minima add up to zero!')

else:

print('Seems OK!')

Suspicious looking maxima!

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-03.csv', delimiter=',')

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.max(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')

elif numpy.sum(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) == 0:

print('Minima add up to zero!')

else:

print('Seems OK!')

Minima add up to zero!

In this way,

we have asked Python to do something different depending on the condition of our data.

Here we printed messages in all cases,

but we could also imagine not using the else catch-all

so that messages are only printed when something is wrong,

freeing us from having to manually examine every plot for features we’ve seen before.

Catching more cases

Note that in the above code example, if the condition to find suspicious maxima is satisfied, we cannot also trigger the condition to confirm whether minima add up to zero. Rewrite the conditional statement from the code above so that both cases can be identified in the same data set.

Solution

We can separate out all the conditional statements, with the final check (‘Seems OK!’) being explicitly conditional on the previous two not being satisfied.

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20: print('Suspicious looking maxima!') if numpy.sum(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) == 0: print('Minima add up to zero!') if (max_inflammation_0 != 0 or max_inflammation_20 != 20) and (numpy.sum(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) != 0): print('Seems OK!')

What Is Truth?

TrueandFalsebooleans are not the only values in Python that are true and false. In fact, any value can be used in aniforelif. After reading and running the code below, explain what the rule is for which values are considered true and which are considered false.if '': print('empty string is true') if 'word': print('word is true') if []: print('empty list is true') if [1, 2, 3]: print('non-empty list is true') if 0: print('zero is true') if 1: print('one is true')

That’s Not Not What I Meant

Sometimes it is useful to check whether some condition is not true. The Boolean operator

notcan do this explicitly. After reading and running the code below, write someifstatements that usenotto test the rule that you formulated in the previous challenge.if not '': print('empty string is not true') if not 'word': print('word is not true') if not not True: print('not not True is true')

Close Enough

Write some conditions that print

Trueif the variableais within 10% of the variablebandFalseotherwise. Compare your implementation with your partner’s: do you get the same answer for all possible pairs of numbers?Hint

There is a built-in function

absthat returns the absolute value of a number:print(abs(-12))12Solution 1

a = 5 b = 5.1 if abs(a - b) <= 0.1 * abs(b): print('True') else: print('False')Solution 2

print(abs(a - b) <= 0.1 * abs(b))This works because the Booleans

TrueandFalsehave string representations which can be printed.

In-Place Operators

Python (and most other languages in the C family) provides in-place operators that work like this:

x = 1 # original value x += 1 # add one to x, assigning result back to x x *= 3 # multiply x by 3 print(x)6Write some code that sums the positive and negative numbers in a list separately, using in-place operators. Do you think the result is more or less readable than writing the same without in-place operators?

Solution

positive_sum = 0 negative_sum = 0 test_list = [3, 4, 6, 1, -1, -5, 0, 7, -8] for num in test_list: if num > 0: positive_sum += num elif num == 0: pass else: negative_sum += num print(positive_sum, negative_sum)Here

passmeans “don’t do anything”. In this particular case, it’s not actually needed, since ifnum == 0neither sum needs to change, but it illustrates the use ofelifandpass.

Sorting a List Into Buckets

In our

datafolder, large data sets are stored in files whose names start with “inflammation-“ and small data sets – in files whose names start with “small-“. We also have some other files that we do not care about at this point. We’d like to break all these files into three lists calledlarge_files,small_files, andother_files, respectively.Add code to the template below to do this. Note that the string method

startswithreturnsTrueif and only if the string it is called on starts with the string passed as an argument, that is:'String'.startswith('Str')TrueBut

'String'.startswith('str')FalseUse the following Python code as your starting point:

filenames = ['inflammation-01.csv', 'myscript.py', 'inflammation-02.csv', 'small-01.csv', 'small-02.csv'] large_files = [] small_files = [] other_files = []Your solution should:

- loop over the names of the files

- figure out which group each filename belongs in

- append the filename to that list

In the end the three lists should be:

large_files = ['inflammation-01.csv', 'inflammation-02.csv'] small_files = ['small-01.csv', 'small-02.csv'] other_files = ['myscript.py']Solution

for filename in filenames: if filename.startswith('inflammation-'): large_files.append(filename) elif filename.startswith('small-'): small_files.append(filename) else: other_files.append(filename) print('large_files:', large_files) print('small_files:', small_files) print('other_files:', other_files)

Counting Vowels

- Write a loop that counts the number of vowels in a character string.

- Test it on a few individual words and full sentences.

- Once you are done, compare your solution to your neighbor’s. Did you make the same decisions about how to handle the letter ‘y’ (which some people think is a vowel, and some do not)?

Solution

vowels = 'aeiouAEIOU' sentence = 'Mary had a little lamb.' count = 0 for char in sentence: if char in vowels: count += 1 print('The number of vowels in this string is ' + str(count))

While loops

It’s worth noting that in addition to for loops which iterate through a set of values to execute multiple iterations of the loop, we can also define a loop based on a conditional statement. These are called while loops. They are not commonly used since they run the risk that if the condition is never satisfied, they can run forever! If while loops are used they should be handled with care, with careful checks that the condition will be satisfied or that the loop can be escaped through some other means (e.g. setting a maximum value of allowed iterations of the loop).

For example, the following while loops have safety escapes built in:

i = 0

while i < 10:

print(i)

i += 1 # Fancy way of saying i = i + 1

else:

print('i is equal or larger than 10')

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

i is equal or larger than 10

The following denotes the kind of while loop that might be used together with some other

function, e.g. in this case a detection algorithm, to loop through some increasing parameter

before giving up the search:

detected = False

i = 1

while not detected:

i *= 2

# We could embed some code here to `detect` what we are looking for, e.g.

# a source in an image where i also sets a pixel range searched over

if i == 8:

print('Halfway')

continue # Skips the rest, starts with the next loop

print(i)

if i == 16:

break # or detected = True

2

4

Halfway

16

Note that break included with a while in this way can (in some situations) lead to ambiguity about what causes the loop to break. We can make the while loop safer if we replace the break statement with an additional condition:

detected = False

i = 1

while not detected and i <= 8:

i *= 2

# We could embed some code here to `detect` what we are looking for, e.g.

# a source in an image where i also sets a pixel range searched over

if i == 8:

print('Halfway')

continue # Skips the rest, starts with the next loop

print(i)

which produces the same output as the previous example.

Key Points

Use

if conditionto start a conditional statement,elif conditionto provide additional tests, andelseto provide a default.The bodies of the branches of conditional statements must be indented.

Use

==to test for equality.

X and Yis only true if bothXandYare true.

X or Yis true if eitherXorY, or both, are true.Zero, the empty string, and the empty list are considered false; all other numbers, strings, and lists are considered true.

TrueandFalserepresent truth values.Conditions are tested once, in order.

whileloops can be used to continue executing a loop, dependent on a conditional statement.